As noted in the about page, I regularly check our sensors to be sure they are within specifications. Over the last couple weeks I have been conducting tests.

Temperature was right on. That’s typical, as our sensor is pretty bulletproof. I have a platinum RTD digital thermometer that’s accurate to within 0.1° F (best to check on a cloudy, windy night to eliminate radiation as a factor). I also have a laboratory-grade aspirated psychrometer with a dry bulb thermometer that’s extremely accurate. It’s analog, so the biggest challenge is reading between the lines. But my tests show the station’s thermal sensor is within 0.5° during the day which is quite good. There’s also a backup sensor on site as well. At night or on cloudy/rainy days, the two sensors are normally within 0.2° F. During sunny days, height (7 ft vs 21 ft) and shielding differences (active vs passive ventilation) can frequently lead to 1° differences in either direction. 2-3° differences are not out of the question when it’s particularly calm and sunny.

Speaking of the psychrometer (“Psychro-dyne”), we have used that to tighten up our humidity correction algorithm. Our sensor has certain nonlinearities in how it measures relative humidity. Luckily, the errors are fairly straightforward and correctable if you have the patience to document the departures. You may notice that our station runs quite a bit drier than most other stations in town (except the Coast Guard) in the middle of the range (30% – 80%). That’s because capacitive humidity sensors tend to get “wetter” (report progressively higher humidities below about 80%) with time and require either replacement or calibration. Most station operators are either unaware, apathetic or unable to do so. Since this station aims to be a reference, we test at all humidities and correct accordingly. I have created custom software libraries to calculate and broadcast these corrected values to this website as well as the National Weather Service (via CWOP network) and Weather Underground. On favorable days, I also spot check our measurements against Sawyer Airport and other official stations (USCG, RAWS, MSU, CRN).

Wind is the hardest parameter to calibrate unless you can levitate 28 feet in the air while holding a weather meter! Instead I use Coast Guard measurements as a reference. Westerly winds (NW, W, SW) are optimal as that’s a vector where air must cross land for both locations (evening the playing field). This station is usually within a few mph of the USCG’s sustained winds/gusts, if not closer.

Although most people don’t pay too much attention to barometric pressure, I consider it to be fundamental to weather observation. All weather forecasting is based on accurate pressure measurements. I like to be able to check the current surface map and see that our MSLP pressure reading matches up, within reason and on appropriate days, to the position of isobars near Marquette.

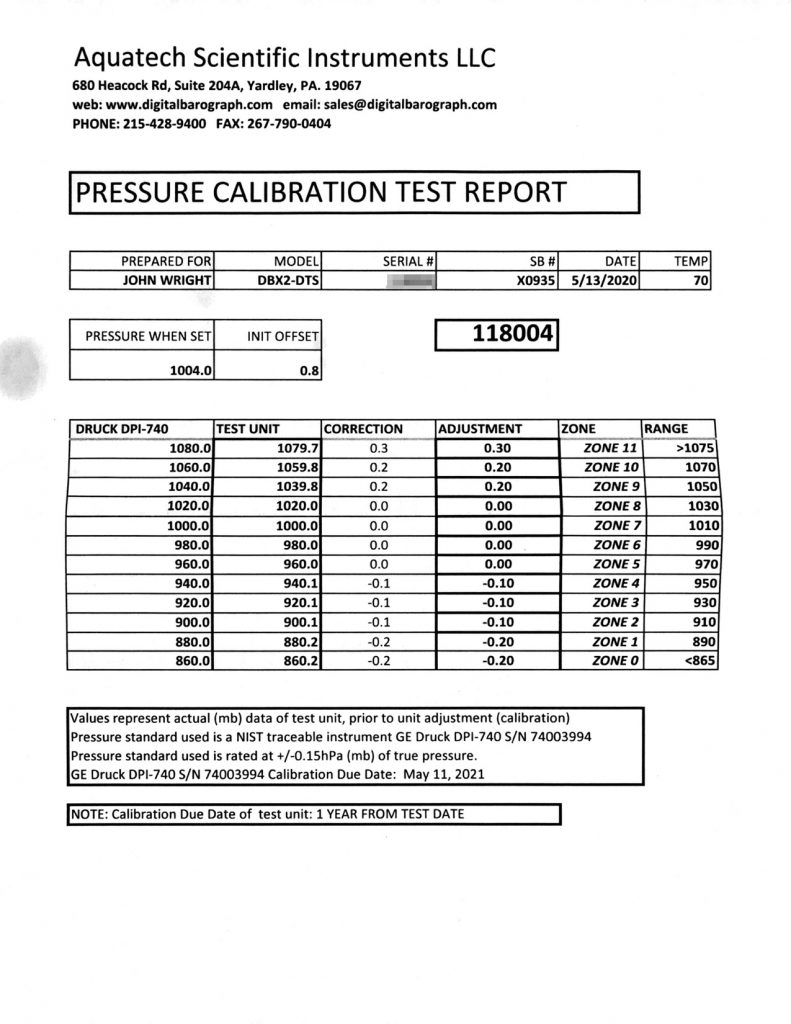

So how do I keep pressure in check? I have an NIST-certified barometer accurate to within 0.007″ Hg. I also take a Kestrel 5000 weather meter down to Sawyer Airport from time to time to check pressure. I record any variances between the two, and then I compare that to my instruments at home. I have even visited the USCG weather telemetry site recently and confirmed with multiple instruments that they match Sawyer Airport. Based on that comparison data, last week I dropped station pressure -0.02″. We now mirror the Coast Guard’s altimeter readings (see update below). Trying to match Sawyer Airport is tricky. Altimeter, particularly at near or below freezing temperatures, is not the same at different elevations. We are 500′ lower than the airport. Also, our MSLP (which is sensitive to temperature unlike altimeter), can be different because Sawyer has a different sub-climate than the city. So, even when atmospheric pressure is the same at both locations, the readings can be different and yet correct!

As for rain, that’s easy, because I keep a manual gauge next to the automatic gauge. I compare those readings daily. Most of the time, they are within 5% of each other so no correction is necessary.

So… that’s all you have to do as a private weather station operator to ensure accurate weather! Simply possess a small arsenal of expensive reference devices, have the time and inclination to run a long series of monotonous tests, learn the theory behind each measurement (combined disciplines of metrology & meteorology), record/process the data correctly, and have the means to adjust what you send out to the world. That kind of rules out the folks who just want something they plug directly into “the cloud” with no fuss (99% of station owners now).

🙂

UPDATE 5/19/19: My reference pressure device (ASI DBX2) returned from re-calibration yesterday. It shows the Coast Guard station running low by 0.02″ (0.8 mb). As I told my wife, there’s no point in acquiring a reference pressure device and paying to have it re-calibrated if you aren’t going to trust it. Who knows the last time a human visited the USCG station or Sawyer’s AWOS equipment. We can prove our readings. We cannot prove theirs.

Here’s the NIST calibration results for the DBX2 (sorry about the smudge):